Commentary May 11, 2020

One (of many) things I’ve learned from the compulsory homeschooling forced upon us by the quarantine is that homeschooling is difficult. Setting aside the environmental and psychological aspects (the role of “parent/teacher” is wildly unpopular in our house for all parties) some subjects, such as English, are quite challenging.

For example, some words are spelled the same but pronounced differently and mean different things (homographs, e.g., dove being a verb with a long “o” as well as a kind of bird with a short “u”) while others are spelled and pronounced the same but can mean multiple things (homonyms). Our favorite example of the latter, and one that is timely, is spike.

The word spike has been in the Formidable zeitgeist for a few weeks now, and it’s a funny word because it can mean about 20 different things, and at least half of those apply to the economy and markets right now.

We’ll set aside spiking the punch for now (it’s not even 10 a.m. yet) and talk about spikes as thin, pointed pieces of matter. In this case, the “corona” of the virus are actually spikes, which serve as its mean to penetrate and infect its victims’ cells.

So, this kind of spike caused another spike, in this case, the volleyball-esque “sharply downward blow” which we saw in the markets in late February through mid-March and are currently seeing in economic readings and corporate earnings for Q1.

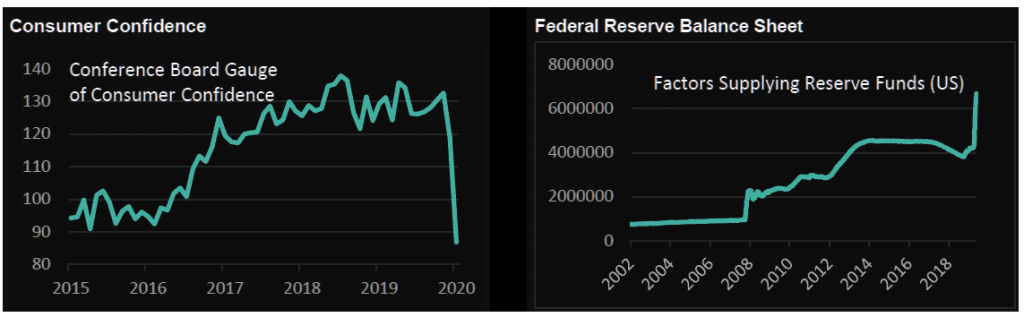

With credit markets seizing at the time, the Federal Reserve spiked (“to suppress or block completely”) rumors of an imminent liquidity crisis through strongly worded statements and actions. In this case, its actions caused a 50% spike (“an abrupt sharp increase”) in its balance sheet, which now stands at over $6.6 trillion.

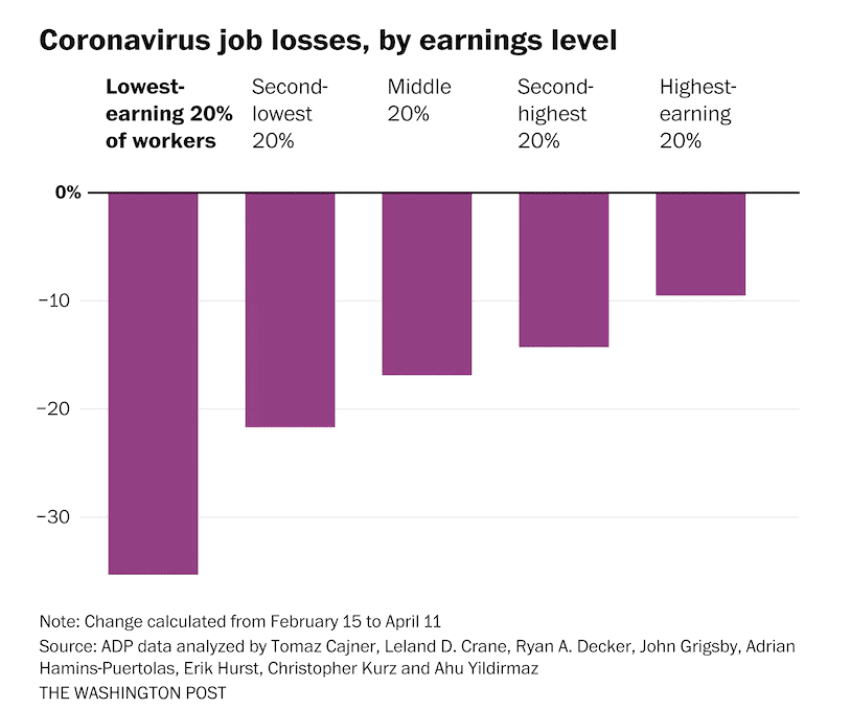

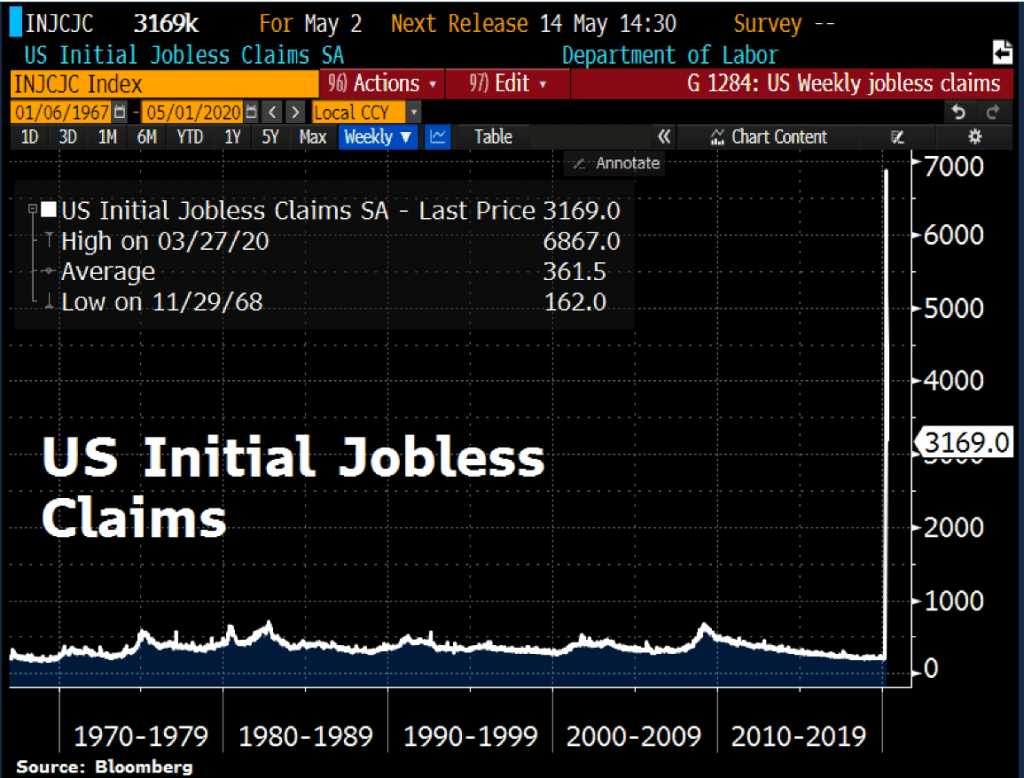

Unfortunately, the reality on the ground in the economy is sobering, with spikes (“an unusually high and sharply defined maximum”) in unemployment (Graph One) reverberating through the economy, especially for employees at the lower end of the wage spectrum (Graph Two). The unemployment rate hit a 90-year high and is likely understated due to a spike in Americans exiting the work force, in some cases due to the perverse incentives of government actions to offset the financial impact of the virus at the household level.

Equity markets, as the cliché goes, look forward, and April’s 12.7% return was the best return for the S&P 500 since 1987; adding on the gains so far for May, we are up over 30% from the market’s bottom on March 23. So, have the Fed and government spiked (“to disable (a cannon) temporarily by driving a spike into the vent”) the cannon that is the business cycle through massive fiscal and monetary stimulus? Here’s where the old cliché that the market is not the economy must be recalled (thanks, NYT).

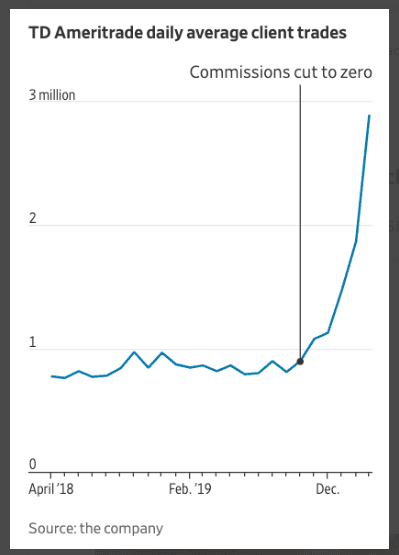

All over the country, people are beginning to emerge from months of sequestration, finally able to put on their spikes (“a pair of shows having spikes attached to the soles”) for a round of golf or their spikes (“spike heel”) for a night on the town. What have they been doing in the interim? Drinking spiked punch, in a manner of speaking. Both the Fed and the Federal government have dumped copious amounts of liquid courage into the mouths of investors. One need look no further than the spike in retail trading (Graph Three) or that three million new retail accounts have opened at Robinhood this year (half by first-time ”investors”) for evidence.

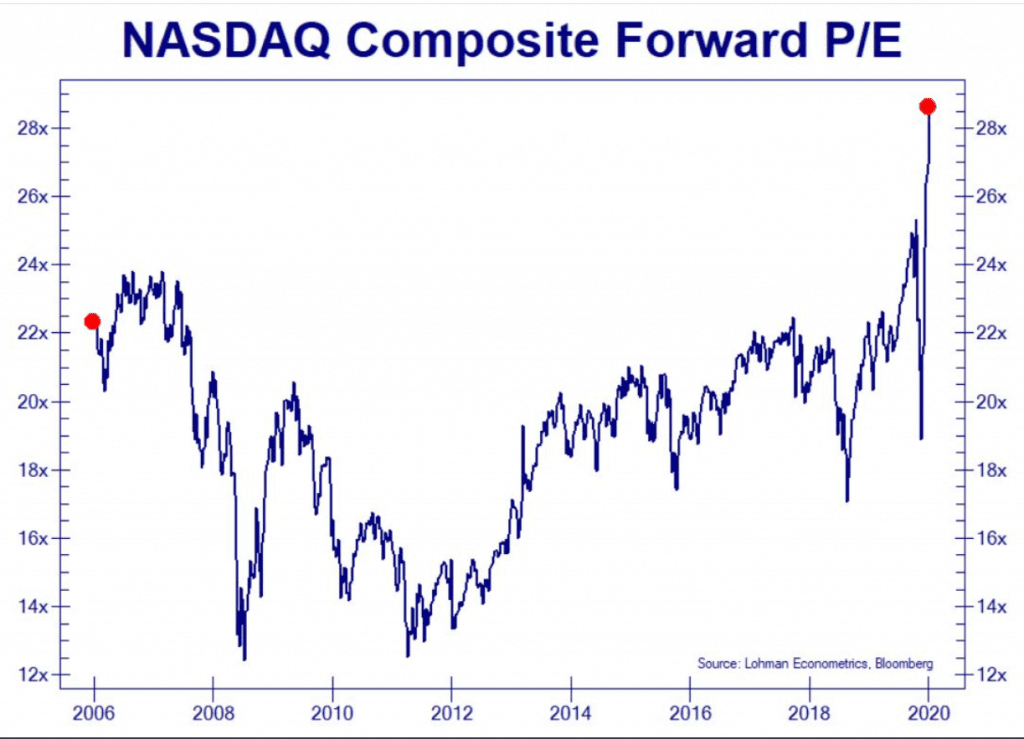

Will the party continue or are we due for the hangover that often follows spiked punch? It’s a conundrum that reminds us of the late 90s. High valuations (Graph Five), albeit this time due, in part, to collapsing earnings, narrow leadership, increasing FOMO (fear of missing out) fueled by retail accounts, wide dispersions between value and growth stocks, and insatiable appetite for stocks with bad business models are all present now.

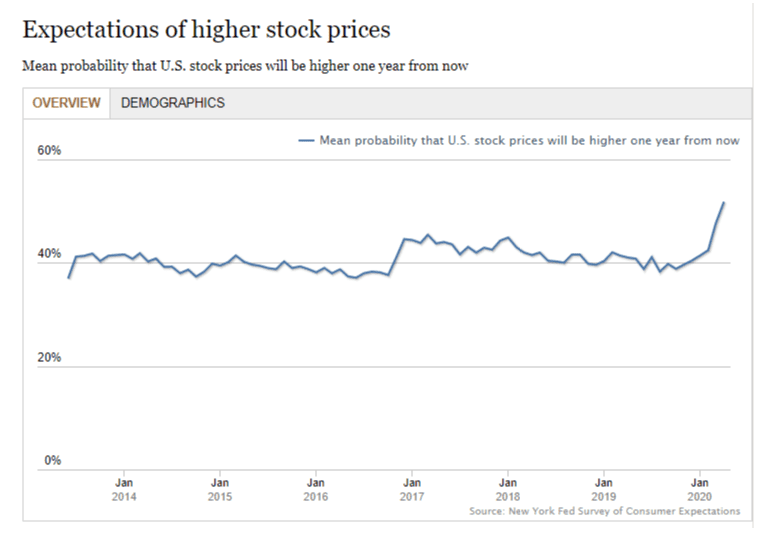

The current disconnect between investor expectations (Graph Five), which shows more than ½ anticipating higher stock prices in 12 months, and plummeting consumer confidence (Graph Six) shows just how divergent the world is.

However, for those of us who didn’t recently open a brokerage account for the first time ever, we remember two important lessons. One, these conditions persisted for years before the tech bubble burst, and that was against a backdrop of a viable alternative from a fixed income perspective (owning long-term Treasuries at yields less than a percent now seems not overly attractive). Second, when the bubble did burst, the market, finally, showed a preference for profitable companies with sustainable business models.

The world is full of spikes (“a very large nail”) and working without a financial advisor is like walking barefoot, which is why we at Formidable are here to help you. Also, for those who want to hear more about our thoughts on the markets, we encourage you to listen to our podcast, Tea (the unspiked kind) and Crumpets, available here.

READY TO TALK?